Introduction

Click! In the 1970s that word signaled the moment when a woman awakened to the powerful ideas of contemporary feminism. Today “click” usually refers to a computer keystroke that connects women (and men) to powerful ideas on the Internet.

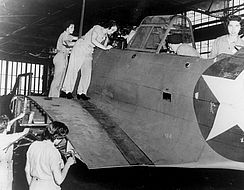

We aim to bridge the gap between those two clicks by offering an exhibit that highlights the achievements of women from the 1940s to 2016. This exhibit explores the power and complexity of gender consciousness in modern American life.

Think of this as a conversation between generations, between men and women, between historians and the public. While the focus is clearly historical, we are not focused exclusively on the past. We believe that the enormous changes in women’s lives need to be better known, both for what was accomplished and for what remains to be done. That is what we mean by “the ongoing feminist revolution.”

Periods of heightened mobilization like the 1960s and 1970s are significant and eye-catching, but social movements don’t start from scratch. Understanding the backstory is just as important as documenting the dramatic moments that caught the media’s attention. Nor do we stop the story in 1975 or 1980 when the media began to lose interest, precisely because women’s issues and women’s lives continued to evolve. Instead, we explain and explore the long history of women’s activism over time. And yet we realize that these changes remain controversial and contested, so we always aim to tell the story from multiple perspectives.

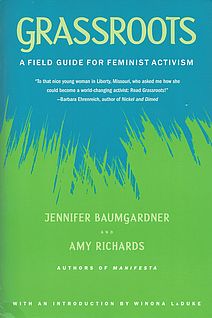

We examine the big national projects and leaders, and we also look closely at the grassroots. We are equally concerned with social change on an individual, personal level and in society at large. We document these ongoing struggles for gender equality in three major areas — the workplace and family; politics and social movements; and the body and health — and, because we are historians, we offer a full library of resources for those who want to learn more. So, get ready to start clicking — in both senses of the word — and prepare to have your historical consciousness raised. First, however, let’s talk about definitions, perceptions and a short history of feminism.

What did Jennifer Lee discover when making a film about feminism?

Excerpt from “Feminist: Stories from Women's Liberation,” a film by Jennifer Lee. (Running time 3:18) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

Feminism: 1. Belief in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes. 2. The movement organized around this belief. (American Heritage Dictionary)

What? Nothing about man-haters? Bra-burners? Ugly old crones with no sense of humor? The list of stereotypes (almost always negative) associated with modern feminism could go on and on. But maybe it is worth pausing to ask: Why has such a seemingly simple and straightforward notion about the equality of the sexes been demonized to such an extent that many Americans shy away from it, even when they admit that they are in agreement with many of its basic goals?

There is no simple answer to that question, although negative portrayals in the media certainly play a huge role; feminists have been characterized as opposing motherhood and families when in fact they do not. But as a result, feminism — the other so-called “f-word”— is not a rallying point or label that speaks to large segments of the population, even to many of the younger women who have come of age in a world reshaped by this far-reaching social movement.

What is the best way to deal with this misperception? Should we abandon the word and try to come up with a gender-neutral term that brings more women and men into the fold? Or should we insist, loudly and boldly, that the word feminism is important and should not be abandoned or scorned? We choose the second option. Indeed, the whole idea behind this project is to showcase the powerful ideas of modern feminism for old and new audiences and to show why feminism mattered in the past and why it is still relevant and necessary today.

As we work to reclaim feminism from the negative stereotypes that have made too many people unwilling to embrace the term, we consciously double our pool of recruits by asserting that feminism is as relevant and potentially life-changing for men as it is for women. Men are essential allies in the feminist struggle and have much to gain when they too move beyond stereotyped gender roles; women cannot and should not do it alone. Feminism supplies a clear road map to a more egalitarian world.

So let’s go back to definitions, realizing that a concept as broad-ranging and capacious as feminism will be hard to reduce to a few key concepts. Instead of focusing simply on the notion of equality between the sexes, let’s go a little deeper, and adopt a definition formulated by Estelle Freedman in her masterful No Turning Back: The History of Feminism and the Future of Women (2002):

Feminism is a belief that women and men are inherently of equal worth. Because most societies privilege men as a group, social movements are necessary to achieve equality between women and men, with the understanding that gender always intersects with other social hierarchies.

The idea of equal worth offers a way to value traditional female priorities like caregiving alongside the work historically associated with men, thus avoiding the trap of assuming that men’s lives are the primary ones women should aspire to in the name of equality. This approach defines feminism not just as an ideology but also as a social justice movement, broadly conceived to include mass action as well as individual participation and thus encompassing a wide range of behavior and beliefs and capable of being equally embraced by women and men. Finally, this complex and nuanced definition recognizes that other factors, especially race, class, and sexuality (i.e., other social hierarchies), intersect with gender to shape women’s lives.

The definition is also broad enough to cover historical changes in the meaning of feminism and feminist movements. Like everything else, feminism has a history. Although women have always been active (if undervalued) participants in history, the specific outlines of feminism began to appear only in the late eighteenth century as part of two broader historical shifts: the rise of capitalism and the spread of Enlightenment ideas about individual rights and the consent of the governed. Those powerful paradigm shifts provided the opening for a tiny but growing number of writers and thinkers, starting with Mary Wollstonecraft in her Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), to ask: What about women? Don’t they have rights and responsibilities too, both as citizens and as participants in a market economy? That is the seed of modern feminism.

Because feminism has such a long history, historians of the United States sometimes resort to a shorthand description that focuses on successive waves of feminist activism. In this model the first wave was the suffrage movement, starting at Seneca Falls in 1848 and culminating in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. The second wave was the revival of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s, when questions of gender equality pushed their way onto the national agenda. In the 1990s, younger feminists began to call themselves the third wave to differentiate themselves from their feminist foremothers. Moving beyond the perceived white, middle-class bias of earlier movements, third-wave feminists embraced a far more racially and sexually inclusive vision; popular culture, more than politics or the workplace, was the focus of their energy, and they defined feminism for themselves rather than through participating in a mass movement. In the twenty-first century, the social-media-savvy generation — for which feminism is never more than a click away on the Internet — uses the blogosphere to generate grassroots social change efforts that are informed by global partners and a broad human rights framework. Young feminists are injecting their voices into popular culture, participating in collective actions and targeting all forms of injustice, such as promoting workers’ rights and opposing sexual violence. Only time will tell if the broad visions of early twenty-first-century feminists can be neatly tucked into something called a fourth wave.

Waves are a useful tool for understanding the history of American feminism, but they also have real limits. Focusing on waves tends to downplay any action or organizing that happens between the periods when feminism is publicly prominent. In addition, the waves perspective makes each manifestation seem to spring from nowhere, rather than locating feminist activism on a broad historical continuum. It also tends to flatten out the story to the most recognizable, public faces of feminism, generally white and middle-class, rather than what historian Nancy Hewitt calls “the messy multiplicity of feminist activism across U.S. history and beyond its borders.” But it is precisely this “messy multiplicity” that necessitates an open-ended, inclusive, and ever-changing understanding of feminism as an ideology and a social movement.

While we embrace this word for its history, we also do so because we believe that looking at the world with a feminist perspective is just as rich and fruitful an approach in the twenty-first century as it was earlier. Any problem or question can be made more complex and challenging by asking: What about women? But as we think about feminism and women’s lives, we always have to be mindful of the difficulties of generalizing about women as a group, given that they are divided by and affected by race, class, sexuality and generations, among other factors. Feminists today embody a range of priorities, diverse programs and multiple perspectives. So when we say women, we should always ask: Which women? Finally, we should all remember that words and labels mean different things to different generations, and embrace those diverse points of view as one of the forces that keep feminism alive and vibrant.

So when someone makes a disparaging remark about feminism, or claims that it has no relevance to her or his life, or that the battles are already over and it’s time to move forward, ask that person: Are you sure you know what feminism really is? Through conversations that cross generations, race, class, and sexual orientation, we can rediscover the true meaning of feminism and explain why it matters, both historically and for the future of women and men, lending the term new significance and reclaiming its proud heritage.

Each section of this exhibit features a timeline with unique content. The timeline materials on this page are relevant to all of the topics in the exhibit and are present in each.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

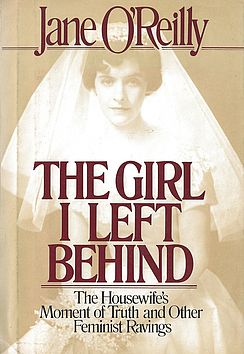

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.