Politics & Social Movements

The Revival of Feminism

What was Rita Arditti’s path to becoming a feminist activist?

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women's Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 2:28) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

How did Arvonne Fraser create a feminist underground in Washington, D.C.?

Excerpt from “Step by Step: Building a Feminist Movement 1941-1977,” a film by Joyce Follet. (Running time 5:36) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

In 1960, the election of John F. Kennedy signaled a new and more public phase for feminists who had been advocating to improve women’s status in the labor force for two decades. At the time, there were no battered women’s shelters, abortion was illegal, want ads in newspapers were divided into “men’s” and “women’s” jobs, and the words sexism and Ms. had not been coined. Not a single university offered a course in women’s studies, and women’s sports programs were small and underfunded. Over the next 15 years, the landscape shifted dramatically. By the end of the decade, women’s issues and feminism seemed to be everywhere, challenging the unequal treatment that women received as citizens and members of families and leading to fundamental social change in the nation’s laws, institutions, and culture. Once sexism had been identified, there was no going back, even when the feminist momentum slowed in the 1980s and 1990s.

Women are human beings — is this a radical idea?

Trailer for “She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry,” a film by Mary Dore. (Running time 2:42) Used with permission. To learn more, visit shesbeautifulwhenshesangry.com. The complete film is available from Cinema Guild.

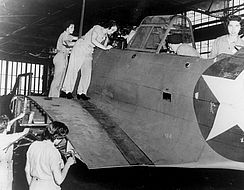

Social movements do not just spring up when leaders announce a set of demands. Preconditions for the revival of feminism lay in the changing social and demographic bases of women’s lives — especially increased labor force participation, greater access to higher education, a declining birthrate, and changing patterns of marriage. Probably the most important factor was the dramatic rise in women working in the postwar years, which undercut traditional gender expectations that women’s primary roles were domestic. To be female in America now usually included education and often a career, as well as marriage and possibly single parenthood after a divorce. These changing social realities created a major constituency for the revival of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s.

Two distinct strands fueled the explosion of interest and energy associated with the revival of feminism on the national level. The first was the women’s rights branch of the movement, best exemplified by the President’s Commission on the Status of Women (1961–1963) led by Esther Peterson, a veteran union activist and assistant secretary of labor, and the founding of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. Women’s rights activists, who were primarily older elite professional women and full-time volunteers, focused on breaking down artificial barriers to women’s advancement, especially through legislation such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Taking a cue from the original manifesto of NOW, they believed it was time “to take action to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partnership with men.”

Why did feminists protest against the Miss America pageant in 1968?

Excerpt from “Miss America,” a film by Lisa Ades. (Running time 2:49) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

Younger, more militant women came to feminism through the civil rights and antiwar movements to form a totally new women’s liberation branch of feminism. The self-confidence and organizational skills they learned in those other movements ran headlong into sexist expectations that they would automatically take notes or serve coffee while men monopolized the leadership roles. Gradually, and often reluctantly, women realized they needed their own movement. Often in or just out of college, these activists did not want to join NOW’s “mainstream”; they wanted to tear the system down, replacing it with non-racist, non-sexist institutions. A symbol of both their humor and their seriousness was the decision to protest the Miss America Pageant in 1968.

How did consciousness-raising promote unity among feminists?

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women's Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 1:13) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

Liane Brandon recalls the revolutionary ideas discussed by the members of Bread and Roses collectives.

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women's Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 2:22) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

Much of the energy of women’s liberation (or “women’s lib” as it was dismissively called) came from its embrace of consciousness-raising groups, where participants came together to share personal stories of their lived experiences as women (“the personal is political”). They inevitably experienced the “click” moment when they realized that other women shared their feelings and that their personal frustrations were not the result of an individual failure to adjust to social and cultural norms but of their secondary status in a male-defined social hierarchy. Brandishing outrage and impassioned rhetoric to make their point, radical women in small groups such as the Redstockings, the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, and Bread and Roses attacked what they saw as a patriarchal, oppressive society that demeaned and devalued women.

In the 1960s these two branches, the more mainstream women’s rights movement and the more radical women’s liberation movement, were fairly small and often quite separate: a career administrator at the Women’s Bureau was not likely to be on the Atlantic City boardwalk throwing her bra into a freedom trash can, nor was a Miss America protestor likely to be testifying before Congress on equal pay legislation. But after 1970, the distinctions between women’s rights and women’s liberation blurred as a rush of new converts flooded the cause. One very public manifestation was the rallies and marches held around the country on August 26, 1970, in honor of the 50th anniversary of winning the vote, as thousands of women took to the streets proclaiming their allegiance to the exciting new ideas of modern feminism.

Initially quite dismissive of this brash young movement, the mainstream media gradually realized that it was not going away. (Women journalists played a key role in raising the consciousness of their male colleagues, although it was an uphill battle.) Even as feminism snowballed as a mass movement, the media felt the need for designated leaders, and two quickly emerged: Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem. Friedan, the author of the best-selling The Feminine Mystique (1963), was already used to the media spotlight, and her authority was enhanced by her election as the first president of NOW. Steinem represented a younger, hipper version of the movement: Herself a journalist and always ready with a witty but pointed quote, she increasingly became feminism’s public face.

Music became part of feminist gatherings and demonstrations and inspired the participants just as it did in the civil rights movement.

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women's Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 0:42) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

The early 1970s were a time of great possibility and optimism. To many participants, it truly did seem as though women were going to change the world. In 1972 Ms. Magazine was founded, and the next year the Supreme Court ruled that abortion was legal in Roe v. Wade. Almost fifty years after it was first introduced, the Equal Rights Amendment passed Congress and was sent to the states for what looked like easy ratification. (Alas, it didn’t turn out that way.) Billie Jean King trounced Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes” tennis match in September 1973. Feminists began to think of themselves as part of a broad, growing, and increasingly influential social movement, symbolized by the title of Robin Morgan’s best-selling anthology, Sisterhood Is Powerful. Only later did the movement grapple with the fact that there were as many things that divided women — such as race, class, age, and sexual orientation — as things that unified them.

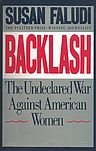

As the civil rights revolution revealed, any movement that poses a powerful challenge to dominant ideas and institutions can provoke a backlash as the issues get thornier and opponents dig in their heels. This began to happen to feminism in the mid-1970s, as symbolized by increasing opposition to the Equal Rights Amendment as well as polarization over reproductive rights. Suddenly the message from the media, which had never been all that supportive in the first place, was that feminism was stalled or in disarray.

It wasn’t. Just because the movement faced new challenges and opposition did not mean that the feminist impulse had died. In the 1980s and 1990s and beyond, feminism continued to evolve in dialogue with what had come before and the pressing new issues of women’s contemporary lives. Now there are at least three generations whose lives have been influenced by feminism since 1960, and each one has much to bring to the table. Encouraging those cross-generational dialogues and continuing to update and adapt the feminist agenda has kept feminism alive, even when the media claims it is dead. And even though there has been a transformational amount of social change in women’s lives since 1960, gender equity and social justice are still far from a reality, which is why feminism is — and will remain — relevant to twenty-first century life.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

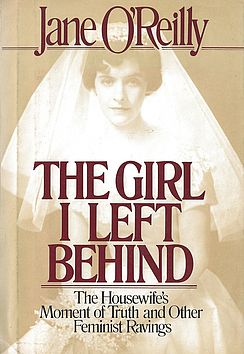

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.