Workplace & Family

Balancing Work and Family

What was Maria Cotera’s “epiphany moment” concerning Chicana activism, work and motherhood?

Excerpt from “A Crushing Love: Chicanas, Motherhood and Activism,” a film by Sylvia Morales. (Running time 3:55) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

If women have always combined work and family in some manner, why does the problem feel so acute and pressing now? Why, fifty years into the revival of feminism, has there been so little progress in securing many of the changes that would help all women working for pay to create their own work–family balance? Why the finger-pointing at feminists, as if their efforts to gain workplace equality are to blame for the problem? These questions have multiple answers, all of them complex. Today, feminists recognize that both women and men often find that their relationship to the paid labor force becomes more difficult and ambiguous when they have children. The lack of social and institutional support makes combining parenthood and paid work an emotional, cultural, and economic challenge. Three issues stand out for parents: the lack of affordable and high-quality daycare, the limited availability of paid parental leave, and the inflexibility of the workplace.

Again, a bit of historical perspective is helpful. When poor and working-class women were forced to seek employment outside the home, they cobbled together a support system of other family members, older children, and helpful neighbors to take care of the domestic and child-rearing chores that were still their major responsibility. This juggling act was seen as an individual problem, and women made do as best they could.

As more women, including more married women, entered the workforce over the course of the twentieth century, the question of balancing work and family became acute. But only when the white middle class ran up against the lack of good daycare and other social services did this even register as a problem, and then just barely. And only when elite women suddenly found themselves struggling to fulfill an unrealistic expectation to “have it all” in their high-powered, highly paid jobs did the media pay attention.

Questions of work–family balance have been on the feminist agenda from the start. In the late 1960s, feminist activists advocated not only for a national network of childcare providers but also for parental leave, paid sick days, and part-time and flexible work hours. But feminist organizations have often found it easier to mobilize public opinion (and raise money) around issues like job discrimination, reproductive freedom, and domestic violence than to agitate and build coalitions for policy changes that would help families strike a work–family balance. And strongly held ideas about motherhood and fatherhood have also made it difficult for feminists to mobilize public support for changes that challenge gender roles in the home. Still, it is puzzling how little success there has been, considering these issues affect so many women and men. The bottom line is that taking care of children and families is still commonly seen as an individual responsibility, not a societal one.

What routinely asked question is at the heart of Governor Madeleine Kunin’s book The New Feminist Agenda?

Excerpt from “Madeleine May Kunin: Political Pioneer,” a film by Catherine E. C. Hughes. (Running time 4:14) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Vermont PBS.

With almost 70 percent of American families now including two working parents, childcare is a pressing problem. And an expensive one, costing as much as 40 percent of a family’s income. Yearly costs average $11,000 per child in a childcare center and can be as much as $24,000 for infants; these costs function like a hidden tax on working families. One study shows that the cost of daycare may explain the increasing number of stay-at-home moms. Another explanation for this increase may be that some mothers (or fathers) feel that staying home and taking care of their children is a more meaningful job, and as a family they’ve decided to adjust to living on a single income. An additional problem is that many daycare workers, most of whom are women, are on the lowest rung of the economic pay scale and the field is affected by high turnover and low possibilities for advancement. In turn, substandard care drives many potential users away. Exasperated parents have summed up the challenge this way: “Finding good childcare is a full-time job. Paying for it is equivalent to a mortgage payment.”

From a policy perspective, the value of instituting universal affordable childcare is a no-brainer: higher disposable income and greater peace of mind for parents; better employment options for workers; and higher-quality childcare for a larger proportion of the population. And yet these arguments have failed to gain much traction except in a few enlightened businesses and corporations, and in the U.S. military.

There was a moment in 1971 when the United States was very close to enacting a national daycare system. A coalition of labor, education, civil rights, and feminist organizations headed by Marian Wright Edelman of the Children’s Defense Fund built bipartisan support for the Comprehensive Child Development Act, which would have established a national system of childcare available to all families on a sliding scale. As social scientists have pointed out, any time a federal entitlement program is offered to the entire population (think of Social Security and Medicare), not just the poor (think of welfare), it has a much better chance of garnering broad political support. But President Richard Nixon vetoed the law and the issue has been basically dead in the water ever since.

Another factor is at work: At all levels of government, the United States has been incredibly stingy in providing benefits that would help working families. The contrast with Western European countries is stark. In France, in addition to four months of paid maternity leave, there is a near-universal free nursery system that enrolls children up to the age of 5. In Denmark, families have options for paid maternal leave for up to a year followed by free or highly subsidized childcare. In contrast, the great breakthrough in the United States, the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act, guarantees job protection and up to twelve weeks of unpaid leave for qualified medical and family reasons, such as the illness of a parent, spouse, or child, or taking care of a newborn or adopted child. Given the country’s deeply engrained tradition of individualism, plus a political climate that makes new spending unlikely, it will take a major effort to build the political will necessary to expand social services for working families. Until then, women and families will continue to muddle through on their own.

Another reason it is so hard to balance work and family is the inflexibility of the workplace itself. In many ways, the typical 9-to-5 white-collar job or 7-to-3 blue-collar job is still set up to match the world of 1960, when the labor force was predominantly male. That kind of “one size fits all” job schedule does not mesh well with a family with children or responsibilities for elder care or sick care. Who picks up the kids after school? How do parents attend school recitals or soccer games? Who takes Granny to her doctor’s appointment? Flexibility on the job can go a long way toward keeping men and women in the workforce while allowing them to also meet the demands and enjoy the satisfactions of family life, but it continues to be the exception rather than the rule.

This brings us back to feminism, and why women — and men — are still struggling with this. Women’s lives have changed dramatically, but societal structures much less so, which means finding the right balance between work and family is an ongoing challenge. In The New Feminist Agenda (2012), Madeleine Kunin, the former governor of Vermont and U.S. ambassador to Switzerland, offered this daunting conclusion: “Until we find a way to sort out how to share these responsibilities — between spouses, partners, employers, and governments — gender equality will remain an elusive goal.”

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

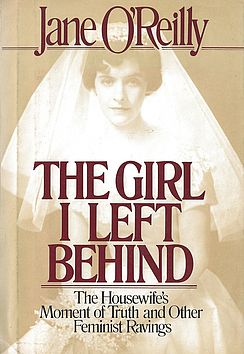

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.