Politics & Social Movements

Grassroots Activism and Coalition Building

How did Gene Boyer become a grassroots feminist activist in the small town of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin?

Excerpt from “Step by Step: Building a Feminist Movement 1941-1977,” a film by Joyce Follet. (Running time 10:16) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

What does Nancy Hawley ask us to remember about the early days of the women’s movement?

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women's Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 0:40) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

Many of the general histories of modern feminism focus on a small group of organizations and leaders, often based in New York and Washington, D.C., and then extrapolate a national story from those sources. The reasons are fairly obvious. Groups like the National Organization for Women, the National Women’s Political Caucus, and the National Abortion Rights Action League received the most attention in the press, as did highly visible leaders such as Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem, and Bella Abzug. In addition, it is often easier to point to specific accomplishments of national groups — laws passed, court cases won, demonstrations organized — as concrete evidence of what the movement has achieved. And yet that gives us only part of the story: a social movement from the top down, rather than the bottom up. How different would the history of feminist activism look from a grassroots perspective?

Examining how feminism played out in the heartland, as discussed in Judith Ezekiel's 2002 book, offers some intriguing perspectives. Starting in 1969, a small but active group of feminists in Dayton, Ohio, created a range of woman-focused institutions, such as childcare cooperatives, a women’s center, and abortion referral services, all basically on their own and certainly not under the direction of any national organization. Instead, many of these initiatives grew out of consciousness-raising groups. Although historians often draw distinctions between the liberal and radical wings of the movement (i.e., NOW versus women’s liberation), in Dayton the situation was far more fluid. The chronology was different too, with the local movement persevering longer into the 1970s and beyond at a time when the national momentum had supposedly stalled.

Local feminist action in Detroit, Minneapolis/St. Paul, and Chicago also does not neatly fit into national categories or timetables. How feminism developed outside the big cities and beyond the East Coast depended on local conditions and concerns. An extremely important determinant in explaining how feminism took shape at the grassroots was geographic location. Space, especially contested space, affected how activists chose their issues and battles, which were as varied as challenging the exclusion of women’s softball teams from publicly funded recreational parks, creating women-friendly spaces like lesbian bars and women’s shelters, and founding women’s bookstores, coffeehouses, and other businesses.

What courageous steps are women taking to confront domestic violence?

Excerpt from “Breaking the Rule of Thumb,” a film by Andrea K. Elovson. (Running time 6:11) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

These women-friendly spaces, in turn, nurtured the emergence of national campaigns, such as the domestic violence and anti-rape movements. As they began to recognize the sexism at the root of male violence, feminists organized safe homes and helping services for victims of abuse and rape. Poorly funded and fraught with local controversy, these centers began the community education necessary to secure state and national funding by the mid-1980s for hotlines, shelters, police training, counseling, and advocacy. Local “Take Back the Night” marches alerted communities that women would resist acts of sexual violence. With the passage of the Violence Against Women Act in 1994, gender-based violence became a federal civil rights offense.

The diversity of feminist action was also evident in local NOW chapters, each of which had a unique history centered on issues germane to members’ lives and communities. In Memphis, NOW was basically the only game in town, so it attracted any women who were drawn to feminist ideas; they in turn used the local chapter to further their specific goals in ways that really didn’t match what was going on in Washington. In Columbus, the NOW chapter prioritized local bread-and-butter concerns such as job equity and rape awareness over national issues like the ERA in an effort to make NOW reflect the interests and concerns of its local members — making it, as chapter organizers put it, “your NOW.” San Francisco already offered a much broader range of progressive organizations, so NOW members used the chapter as a way to build bridges and coalitions with other like-minded feminist activists on a variety of material rights, such as daycare, reproductive rights, and job discrimination.

Coalition building has always been important to the feminist movement. There was much crossover between the feminist movement and other social justice movements before, during, and after the 1960s and 1970s, especially concerning peace, the environment, consumer issues, and welfare rights. Just as feminist theory talks about the intersectionality of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation, activists rarely limit themselves to just one issue. Instead, almost any item on the feminist agenda intersects with a range of other progressive causes, necessitating coalitions and bridges between them. In all these movements, women, primarily at the grassroots level, were often the driving forces for social change.

Try to imagine a multidimensional map of feminist activism in the 1970s and beyond. Instead of one-way lines of influence from the national to the state to the local, you would be likely to see lines going in the other direction, or multiple directions. Instead of illustrating a presumption that feminist ideas moved primarily from the East Coast westward and southward, it would highlight the groundswells of activism and connections that appeared spontaneously at widely dispersed spots across the country. And the graphic would show change over time, specifically how much of this local activism continued long after the national movement had supposedly stalled. If such a map could be created, it would show feminist activism in all its true complexity.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

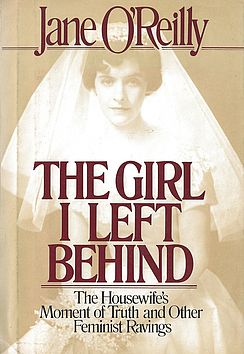

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.