Workplace & Family

Challenging Sex Discrimination

In the 1970s, “white-collar” office workers organized their own union, 9to5, while activists like Mercedes Tompkins supported women moving into “blue-collar” trades.

Excerpt from “A Moment in Her Story: Stories from the Boston Women's Movement,” a film by Catherine Russo. (Running time 1:49) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Catherine Russo Documentaries.

In 1952 the United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers of America published a pamphlet titled “UE Fights for Women Workers,” a primer for battling wage discrimination on the job. No author was listed, but it was later attributed to labor journalist Betty Goldstein, soon to be much better known as Betty Friedan, the author of the groundbreaking 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. Female labor activists had long been aware of the pervasive patterns of sex discrimination in the workplace, especially in terms of unequal pay and limited opportunities, but attacking the problem had been an uphill battle. An early victory was the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963, one of the recommendations of the President’s Commission on the Status of Women. A much bigger step forward occurred with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The story has been told many times, and the details vary, but how sex joined the categories of race, religion, and national origin in Title VII prohibiting employment discrimination is quite a tale. It illustrates the difficulty of unraveling knotty issues when racism and sexism get tangled together. And it reveals the divisions between women over what was perceived to be in their best interest. Virginia legislator Howard W. Smith, an avowed segregationist, moved to add the word sex to the pending civil rights legislation hoping to hasten its defeat. Michigan Representative Martha Griffiths, one of the few ranking women in the House, also believed that sex should be included. For her, guaranteeing the rights of black men and women would, in no uncertain terms, disadvantage white women. Oregon Representative Edith Green argued against adding sex. She was concerned that the legislation would deprive women of the benefits of protective labor laws. Griffiths’s argument won the support of all but one of the twelve women in the House and went to the Senate. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was ultimately passed with sex included, and Title VII has been a cornerstone of all women’s employment rights ever since.

But that was only stage one of the fight. The next was to get the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) to enforce the law. Even though 37 percent of the initial complaints concerned sex discrimination, the EEOC prioritized civil rights for African Americans, not civil rights for women. Frustration with the EEOC’s foot-dragging led to the formation of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966, which immediately took legal action forcing the EEOC to fulfill its mandate.

Among the first groups of women to come forward were flight attendants, then called stewardesses, uniformly female and subject to a range of arbitrary and demeaning rules about their weight (no more than 135 pounds), appearance (attractive), marital status (single), and mandatory retirement age (thirty-five). The airline industry defended its policy as necessary to cater to its clientele of predominantly male business travelers, which memorably caused Representative Griffiths to ask, “What are you running, an airline or a whorehouse?” Under EEOC pressure, the airline industry did change its rules.

The limits of Title VII led indirectly to the passage of Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. Title VII did not cover educational institutions, which meant that women faculty, staff, and students had no legal basis to challenge the rampant sex discrimination on their campuses, such as quotas on admissions and discriminatory hiring and salary procedures. While Title IX’s greatest impact has been in expanding opportunities for women’s sports, the original impetus behind the law was challenging sex discrimination in higher education overall.

At the same time that legislation gave women the tools to fight sex discrimination on the job, court challenges also significantly expanded their rights. One force behind these challenges was NOW’s Legal Defense and Education Fund; another was the Women’s Rights Project, funded by the ACLU and headed by a young law professor named Ruth Bader Ginsburg. For example, Weeks v. Southern Bell (1966) struck down an employer’s ban on hiring women for jobs that involved lifting anything heavier than thirty pounds (the weight of a toddler, mothers quickly pointed out). Phillips v. Martin Marietta (1971) ruled that an employer could not deny a woman with small children a job if men were not treated the same way. Later on, the Supreme Court ruled in California Federal Savings and Loan Association v. Guerra (1987) that pregnancy was a temporary disability, which guaranteed women time off for childbirth and gave them their original jobs back when they returned to work. These cases seem straightforward, almost commonsense to us now, but it was extremely difficult to break through years of judicial precedent that had treated women as needing special protection on the job.

In their movements, women of color — African American, Chicana, Mexican American, Native American and Asian American — became effective advocates for more equitable pay scales and services for working mothers and families. After the presidential administration of Lyndon Johnson began its War on Poverty, they found allies in some state offices of economic development. But it was mainly in autonomous organizations where women worked out their strategies for improving their economic situation and that of their families. The Chicana Service Action Center, established in 1972, was especially important in helping Mexican-American women living and working in East Los Angeles.

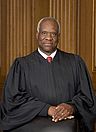

What lie does Gloria Steinem say ignited the conflagration between Anita Hill and Clarence Thomas?

Excerpt from “Sex and Justice,” a film by Julian Schlossberg and Seymour Wishman. (Running time 4:55) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Westchester Films, Inc.

What landmark 1976 jury trial, argued by attorney Allyn Ravitz, helped to define sexual harassment?

Excerpt from “Passing the Torch,” a film by Carol King. (Running time 3:11) Used with permission. The complete film is available from King Rose Archives. For more information, visit Veteran Feminists of America.

Another important legal tool was the definition of sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination. We have feminist scholar Catharine MacKinnon to thank for articulating the legal argument behind the link (basically that a hostile work environment discriminates against women) and then playing a leading role in Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson (1986), wherein the Supreme Court recognized the legal standing of the concept.

Sexual harassment in the workplace took center stage at the confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas for the Supreme Court in 1991. Testimony by Oklahoma law school professor Anita Hill, who had been Thomas’s subordinate at the Department of Education and the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission in the 1980s, illustrated a pervasive pattern of inappropriate behavior on the part of her boss, including pressure to date him socially as well as discussions of pornography and sex during meetings in his office. Even though she felt extremely uncomfortable, Hill did not quit her job, which was important to her professionally. Despite her courageous decision to come forward, the all-male Senate Judiciary Committee voted to confirm Thomas, evidence, many women believed, that “they just didn’t get it.” In direct response, a record number of women sought and won political office in the 1992 elections.

In this survey of legislative and judicial attempts to combat sex discrimination on the job, pride of place goes to the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009. Here is one story that truly did have a happy ending — eventually, and, it should be noted, forty-six years after the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Lilly Ledbetter had worked as a supervisor in a Goodyear Tire assembly plant in Alabama since 1979, but only as she neared retirement did she realize she was being paid significantly less than male colleagues with similar seniority and experience. She successfully sued Goodyear for back pay and damages, but the judgment was overturned by the Supreme Court in 2007 on a technicality: Her suit had not been filed within 180 days of her initial employment. In response, Congress passed legislation that restarted the 180-day clock every time a discriminatory paycheck was issued. Showing both its symbolic and substantive importance, this was the first law that President Barack Obama signed when taking office. And Ruth Bader Ginsburg, now a Supreme Court justice, put a framed copy of the bill in her chambers.

Labor movement feminists also broke new ground in the fight against sex discrimination in the workplace. Historian Dorothy Sue Cobble has called these activists “the other women’s movement.” Acutely aware of how questions of race and class intersect with gender on the job, feminist labor activists have tried to improve conditions for women through collective bargaining and by promoting greater representation in labor leadership. Top priorities include healthcare benefits covering pregnancy, equitable pay scales, and access to training for higher-paying jobs.

Unfortunately, the labor movement has been hampered by a dramatic decline in overall union membership since its post–World War II high: 11.3 percent of the nation’s workers belonged to unions in 2012, down from a peak of 35 percent in the mid-1950s. But women make up a hefty 44 percent of those union members, a reflection of the long-term shift away from heavy industry (primarily male, the source of the first wave of union members) and toward a service economy (increasingly female). Indeed, the areas of strongest growth for the labor movement have been sectors where women predominate, with public-sector unions of government and municipal workers like the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) leading the way.

The clerical union 9 to 5 is familiar to many as the inspiration for the 1980 movie starring Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton, but the real story is just as compelling. It had its roots in a newsletter published in 1972, “9 to 5 News.” A year later, activist Karen Nussbaum and a group of women office workers in Boston realized that clerical workers were a vast and almost invisible sector of the workforce, not incidentally one that was almost exclusively female. They formed the first 9 to 5 as a collective effort to protest workplace discrimination, including low wages. Nussbaum enlisted the cooperation of the SEIU to give the young organization bargaining power; 9 to 5 formed local 925. Male leaders doubted that clerical workers would join a union, but Nussbaum proved them wrong. Local clerical and service worker unions sprang up all over the country demanding equal pay, maternity benefits, opportunities for advancement, and an end to doing personal errands for bosses.

Karen Nussbaum went on to serve as head of the Women’s Bureau in the Clinton administration, and then as executive director of Working America, an affiliate of the AFL-CIO with three million members. After three decades on the front lines of labor organizing, she notes both continuity and change: “The pressure cooker of discrimination against women in the workplace was released by allowing highly educated women to track into professional jobs. It was a safety valve, and so the impulse to organize was reduced because higher-level women got more of what they wanted, but they got it on an individual basis, rather than a collective basis.” In contrast, the vast majority of female workers still struggle to hold on to jobs and benefits, especially in a poor economy, just like male workers. In that sense only, the modern economy is an equal opportunity employer.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.