Workplace & Family

Women’s Work

How did activist Dolores Huerta grapple with the dual roles of motherhood and total commitment to social justice and political change?

Excerpt from “A Crushing Love: Chicanas, Motherhood and Activism,” a film by Sylvia Morales. (Running time 4:37) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

Here is one of the few generalizations that applies to all of women’s history: Women have always worked. The kinds of work that women have performed and which women are working have changed over time, but women’s contributions to the economy, in both unpaid domestic labor in their families and wage labor outside the home, are immense.

To understand the monumental changes in women’s lives since the 1960s, especially the ongoing struggle to balance work and family, it helps to step back and look at the question of women’s work from a historical perspective. That of course would be a huge topic, so let’s limit our focus to the onset of industrialization in the nineteenth century. In predominantly agricultural societies, men and women (and their children) worked together in a family unit. As the economy grew and diversified, men increasingly left their households to work for pay. In fact, being the breadwinner for the family became a primary definition of the male gender role.

But where did that leave women? They were working too, at the same domestic tasks they had always performed, mainly running households and supervising children. But this work was not paid wages, which had the result of rendering it practically invisible in a new economic structure that focused on waged labor. Keep this idea of unpaid domestic labor in mind as the story of women’s work unfolds.

Soon some women, almost exclusively single, joined men in the paid labor force. The best-known examples are the Lowell mill girls, who left New England farms in the 1830s and 1840s to work for low wages in the new textile mills. By the early twentieth century, approximately 20 percent of all women were in the labor force. They were primarily young (age 14 to 20), single, and from immigrant or working-class backgrounds; waged work was a temporary life stage before marriage. Very few white married women (less than 3 percent) worked outside the home at this point. All of them, however, were helping keep their families afloat by their unpaid domestic labor. For many working-class women, domestic labor was not enough to help make ends meet, so they found creative ways to bring in money while remaining within the home. In the African-American community, the wages available to men were so low their wives were often forced into the labor market, largely as domestic servants.

Why did Dorothy Haener become a labor activist after World War II, when women were a minority in labor unions?

Excerpt from “Step by Step: Building a Feminist Movement 1941-1977,” a film by Joyce Follet. (Running time 4:33) Used with permission. The complete film is available from Women Make Movies.

For the rest of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, there was a steady expansion of women in the workforce, from just over 20 percent in 1920, to 35 percent in 1960, to 60 percent in 2000, to 77 percent in 2011. This rise in the number of single and married women workers occurred at a steady pace, but key events contributed to the overall increase. During the Great Depression, women took paid jobs outside the home to help their families. After the outbreak of World War II, government and industry encouraged women’s employment in both traditional and nontraditional fields. In the postwar era, when women were encouraged to return to the home, almost 30 percent of American married women were still employed to meet family needs. The expansion of women’s educational opportunities during the 1960s and 1970s provided women with new paths into the workforce. The civil rights movement brought attention to black women’s work lives while the feminist movement raised questions about the very nature of work for women. Work became an area of life that could be more than a burden to be borne; it could become an avenue for personal growth and economic independence. The history of women and work in the twentieth century shows that the increase in the numbers is a result of an economic demand for women workers and, at the same time, women’s desire to work. To grow, the U.S. economy needed women.

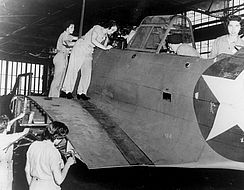

Meet the tradeswomen in Maine who helped build Liberty Ships during World War II.

Video, “On the Job: Women Launching a New Tradition,” by Spring Point Media Center. (Running time 27:06) Creative Commons license. The video is available from the Maine Community TV Archives.

Perhaps the most interesting figure is the increase in married women working in the paid labor force. In 1920, about 9 percent of married women were in the workforce. That number grew about 2 to 3 percent in the next two decades. Not surprisingly, the number increased more dramatically during the World War II era, from 14 percent in 1940 to 22 percent in 1950. What is surprising is that the percentage continued to grow despite the 1950s cultural emphasis on domesticity that encouraged married women, especially those with children, to stay out of the workforce. In 1960, 31 percent of married women worked, and the percentage increased steadily until by the year 2000, about 62 percent of married women worked.

Today, defining women in the workplace as either single or married, part time or full time, with or without children is a data analysis nightmare. But what all the trends suggest is that for most of their lives, the majority of women will earn a living outside the home, just as men do.

This history is important because the steady revolution in women’s lives outside the home was not accompanied by any major changes and renegotiations of their lives inside the home. Women’s new work roles were simply grafted on top of their traditional domestic chores, producing what sociologists call “the double shift.” Whereas men were still defined primarily by their roles as workers, women were stuck (in the words of one harried female worker) with “two full-time jobs instead of just one.”

One of the most salient characteristics of the modern economy is how deeply it is segmented by gender: Work is still divided roughly into women’s and men’s jobs, with very little crossover between them. While specific jobs and sectors of the economy have changed over the course of the twentieth century, gender segmentation has not. Today, despite the opening of many men’s jobs to women (think of bus drivers, construction workers, and police officers), approximately 75 percent of women still work in predominantly “female” occupations.

Domestic service has always been gendered female, and the history of that field offers an interesting window on the changing racial and ethnic makeup of the workforce. At first native-born white women worked for wages in other women’s homes, but with the arrival of Irish immigrants in the mid-nineteenth century, the field became so identified with the Irish that “Brigid” was practically synonymous with servant. In the post–Civil War South, literally the only role available to African-American women was domestic service well into the twentieth century. Over time they were joined or supplanted by other minority groups: Chinese immigrants on the West Coast, Mexican-Americans, and more recently, immigrants from Southeast Asia and South America. Today domestic service remains predominantly female and at the very bottom of the occupational ladder.

A definite notch up was industrial work, which often involved factory work in areas such as textiles and garment production, as well as food processing and canning. In any industry, the better jobs were reserved for men, generally white, while women, again mostly white, usually clustered in a specific set of jobs that had been deemed “women’s work.” When these industries were first unionized, it was the needs of male workers as family breadwinners that took priority, not those of female workers, who were seen as temporary. But women workers repeatedly demonstrated that they too wanted to join unions, and organized labor took note.

Next up the occupational rung was clerical, sales, and administrative work, which began to open up to white women in the late nineteenth century. Previously clerks and secretaries had been men; the typewriter changed that, drawing middle-class women into the workforce. Even though these jobs often paid little more than industrial jobs, they were greatly desired because they were “white-collar” and thus promised higher status and possible occupational mobility. As corporations and business organizations grew over the course of the twentieth century, women’s importance as clerical workers grew as well. A quick glance around any office confirms that the modern economy would collapse without women.

Another area of growth, especially in the post-industrial economy, was the personal service sector, which encompasses jobs such as waitress, hairdresser, beautician, florist, and babysitter and daycare provider. To distinguish it from white-collar (professional) work and blue-collar (industrial) work, this sector is tagged pink-collar work, and its practitioners are almost exclusively female. Showing its lack of possibilities for advancement, it is often referred to as the pink-collar ghetto.

Ascending the occupational pyramid, women who aspired to professional jobs were generally channeled into teaching, nursing, social work, and librarianship. At first it was native-born white women who got those jobs, but later they became avenues of upward social mobility for other groups. And at the very top were the elite professions, such as medicine, law, finance, and corporate management. While women have made great strides in fields such as medicine and law since the 1970s (they’ve gone from receiving 10 percent of medical degrees in 1977 to 46 percent in 2010, and from receiving 22 percent of law degrees to 47 percent in that period), their numbers in the upper echelons of the corporate world have lagged. The barriers women face in the modern business world (only 3 percent of Fortune 500 companies are led by women, and women make up only 17 percent of corporate boards) have led to the familiar image of a “glass ceiling” limiting their advancement.

Along with women’s work went women’s salaries, always lower than men’s, but at least there is some progress on that front. In the 1970s some feminists wore buttons that simply said “59¢,” a reference to the fact that women working full time on average made only 59 cents to every dollar earned by men. By 2002 the figure had risen to 77 cents; by 2013 it was up by one additional cent. The Institute for Women’s Policy Research estimates that the typical female college graduate will earn $440,000 less than her male colleagues over a twenty-year period. That is some serious coin.

On a more positive note, entrepreneurial women have boldly ventured into the business world. Since 1997 the number of women-owned businesses has increased 68 percent. The passage of the Women’s Business Ownership Act of 1988 removed some of the significant barriers for women’s enterprises. For many women, owning a business provides a means of balancing work and family.

So that is a snapshot of how women’s roles in the modern economy have changed over time. Today, progress for women is evident. Women have more work options, and some women earn more than men holding similar jobs. Yet the problem of wage inequality between men and women still exists, and the wage gap between women at the top of the scale and those at the bottom has widened. Enhancing economic security for all women and their families, and combating the exploitation of women workers who are most vulnerable to workplace abuses, continue to be at the top of the feminist agenda.

How to Navigate our Interactive Timeline

You will find unique content in each chapter’s timeline.

Place the cursor over the timeline to scroll up and down within the timeline itself. If you place the cursor anywhere else on the page, you can scroll up and down in the whole page – but the timeline won’t scroll.

To see what’s in the timeline beyond the top or bottom of the window, use the white “dragger” located on the right edge of the timeline. (It looks like a small white disk with an up-arrow and a down-arrow attached to it.) If you click on the dragger, you can move the whole timeline up or down, so you can see more of it. If the dragger won’t move any further, then you’ve reached one end of the timeline.

Click on one of the timeline entries and it will display a short description of the subject. It may also include an image, a video, or a link to more information within our website or on another website.

Our timelines are also available in our Resource Library in non-interactive format.

Timeline Legend

Yellow bars mark entries that appear in every chapter

This icon indicates a book

This icon indicates a film

1971 The Click! Moment

The idea of the “Click! moment” was coined by Jane O’Reilly. “The women in the group looked at her, looked at each other, and ... click! A moment of truth. The shock of recognition. Instant sisterhood... Those clicks are coming faster and faster. They were nearly audible last summer, which was a very angry summer for American women. Not redneck-angry from screaming because we are so frustrated and unfulfilled-angry, but clicking-things-into-place-angry, because we have suddenly and shockingly perceived the basic disorder in what has been believed to be the natural order of things.” Article, “The Housewife's Moment of Truth,” published in the first issue of Ms. Magazine and in New York Magazine. Republished in The Girl I Left Behind, by Jane O'Reilly (Macmillan, 1980). Jane O'Reilly papers, Schlesinger Library.